Reconstruction Vignettes

In every region of the United States, movements for multiracial democracy and justice arose, redefining freedom and contending with white supremacy. Featured here is a selection of stories — teachable vignettes, with primary and secondary sources — from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. By example, they demonstrate that the story of Reconstruction extends beyond the South. Our resources page offers more materials to learn about Reconstruction, including books, lessons, podcasts, and digital archives.

ALABAMA

| Black Mobilians established a local newspaper, the Nationalist. They viewed sustaining a newspaper as essential to their quest for educational access and legitimacy. Although white American Missionary Association educators served as editors from Montgomery, the Nationalist had a trustees’ board composed entirely of African Americans and a few Creoles of color. In addition to news coverage, the newspaper placed an emphasis on literacy and citizenship building. John Silsby, the first editor, proclaimed that the advancement of literacy through a newspaper constituted the “new state of things.” He also promised that the Nationalist would contain “a variety of instructive and interesting matter. . . inculcating the truth that true religion and the virtues that germinate in it, are the only foundations of individual and national happiness.” To this end, the newspaper featured a children’s section, short stories, poetry, advertisements for literary societies and school events, and coverage of local, state, and national events. The Nationalist quickly became an important organ for Black Mobilians educational quest. |

In the fall of 1865, African Americans in Mobile, Alabama, established the Nationalist newspaper. It served as a vehicle for civil rights advocacy and community enrichment for the rest of the decade.

Source: Educational Reconstruction: African American Schools in the Urban South, 1865-1890 by Hilary Green

ALASKA

| What will the government of this ice-covered desert cost? It was stated at the War Department yesterday that it would require a regiment of infantry. It costs $1,100 a year to maintain a single soldier in Washington. It would cost twice as much in Seward’s desert. It costs $1,000,000 a year to keep a man-of-war at sea. We should have to have at least six on the 3,000 miles of Seward’s coast, as naval men say here. We should have to institute a territorial government. What wouldn’t that cost? Indian wars would inevitably follow. They could not be avoided. On the Nebraska plains it now costs us $115,000 to kill one Indian. It would cost $300,000 a head to kill Seward’s Indians. There is not, in the history of diplomacy, such insensate folly as this treaty. |

During Reconstruction, the federal government increasingly channeled its resources and military power into western U.S. expansion and settler colonialism. On April 9, 1867, the New York Tribune published an editorial opposing the Alaska Purchase Treaty. The U.S. had agreed to purchase Alaska from the Russian Empire two weeks prior, at the direction of Secretary of State William H. Seward. Many Republican elites and industrialists saw acquisition of the Alaskan coastline as a means to expand the westward reach of U.S. sovereignty and capital, with new opportunities for whaling and growing trade in Asia. The author of this article vehemently opposed this purchase, but did not take umbrage with the cruel practices of settler colonialism and Native displacement. Rather, as excerpted here, he was concerned with the possible economic cost of genocide. Opponents of this acquisition often called it “Seward’s Folly,” believing that the federal government had made an economic blunder and acquired resource-poor land. These criticisms would abate in the 1890s, with the discovery of gold in Yukon.

Source: Chronicling America

Arizona

This is a cabinet card of Samuel Bridgewater, who joined the 24th Infantry Regiment in the 1880s and spent part of the 1890s as a Buffalo Soldier at Fort Huachuca in present-day Arizona. Buffalo Soldiers were members of postwar Black regiments, who the federal government deployed to the Great Plains and Southwest to support U.S. expansion and settler colonialism. They built infrastructure and defended U.S. settlements, often tasked with fighting Indigenous people in the name of a country that refused equal rights to people of color. Despite battling the Confederate insurrection during the Civil War and strengthening U.S. sovereignty during Reconstruction, Black soldiers faced white supremacist policies and terror from federal officials and civilians alike.

Source: National Museum of African American History & Culture

Arkansas

| In several counties, local bureau agents reported employers' efforts to defraud freedpeople working on shares when the time came to divide up crops and settle debts. In others, landowners and laborers argued over pay for work done on plantations after crops were “laid by.” In addition to poverty and labor conflict, in many areas freedpeople were terrorized by the violence of white “lawless characters” given free rein by local law enforcement officials, still in place in practice even if now subordinate to federal military authority. Under these circumstances, freedpeople sought an effective voice in governmental affairs to free themselves from the crush of landlords’ control, to address economic exploitation, and to protect their communities from violence. Political mobilization had, of course, a clear and practical end. |

In 1866 and 1867, poor weather and inadequate crop yields in Arkansas deepened debts and disputes over unpaid wages. Mass political mobilization was critical to uplifting and empowering Black communities in the public sphere.

Source: Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South by Hannah Rosen

california

On Oct. 30, 1871, the New York Herald shared news of a massacre in Los Angeles the week prior. A police officer and a civilian had intervened in a feud between two Chinese mutual benefit association leaders and were fatally shot. A mob of roughly 500 people responded by robbing and murdering 19 Chinese residents, including children, in what became one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history. The dispute that day in Old Chinatown may have been the immediate catalyst for the massacre, but anti-Chinese sentiments grew dramatically alongside increases in Chinese immigration to California. Many local officials and civilians alike resorted to discriminatory laws and violence to maintain a white supremacist social order and bar Chinese residents from the benefits of citizenship.

Source: Chronicling America

colorado

On Jan. 3, 1878, the Georgetown Courier in Colorado reported that a local group of Black Masons had visited an opera house with friends to ring in the new year.

connecticut

| Although born and raised in Connecticut, yes, and lived in Connecticut more than three-fourths of my life, it has been my privilege to vote at five Presidential elections. Twice it was my privilege and pleasure to help elect the lamented and murdered Lincoln, and if my life is spared I intend to be where I can show that I have the principles of a man, and act like a man, and vote like a man, but not in my native State; I cannot do it there, I must remove to the old Bay State for the right to be a man. Connecticut, I love thy name, but not thy restrictions. I think the time is not far distant when the colored man will have his rights in Connecticut. |

James Mars (1790-1880)

Source: Connecticut Historical Society

James Mars was born into slavery in Connecticut at the end of the 18th century and worked to buy his way to freedom. His 1864 autobiography, Life of James Mars, A Slave Bought and Sold in Connecticut, recounted the story of his enslavement and enfranchisement. Mars updated the text in 1868, concluding with this paragraph on continued limitations to voting rights in his home state. Connecticut ratified the 15th Amendment the following year.

Source: Documenting the American South

Delaware

| From our population of over twenty thousand souls, or nearly one-fifth the entire population of the State, the Legislature does not provide a solitary school, nor appropriate a single dollar of State money. We hold this discrimination as against the genius of government; insulting to the laws of Congress; detrimental to the best interests of the State, and outrageous to the colored tax payers. We say against the spirit of the age, because non-progressive in its character and in the interests of ignorance; because tending to perpetuate poverty, multiply crime, and aid in human degradation. . . . This discrimination is outrageous to the colored people, because it is sullen opposition against their rights as citizens. It is founded upon no principle, backed by no argument, but sustained entirely by a prejudice founded upon a long course of false education. |

On Jan. 9, 1873, Delaware’s Convention of Colored People gathered in Dover to discuss and demand state provisions to educate their children. They adopted a resolution, excerpted here, condemning schooling discrimination in Delaware and asserting their rights as citizens and taxpayers to the benefits long provided to white residents.

Source: Colored Conventions Project

district of columbia

In January of 1869, representatives from Black communities around the country gathered in Washington, D.C., for a national convention. Delegates analyzed and debated a number of issues tied to the promise of freedom, including labor and land rights, access to quality education, political and legal representation, and the role of the Black press in the advocacy and advancement of multiracial democracy. The meeting in D.C. built on decades of discussions in the Colored Conventions movement, formed in 1830. Notably, women appear prominently in this sketch of the January 1869 convention. Despite their critical roles in these spaces and the wider Black freedom movement, they were often relegated to the margins of meeting minutes and proceedings.

Source: Library of Congress

florida

| Dear Sir, We the undersigned, colored grocers of this city, take this method to Present themselves to you. We Protest against the crushing Taxes that are charged by the civil authorities as unbearable, under the circumstances. If we do not keep such astablishments to Protect our People against Paying the Rebels such a high Price for what they need what will they have at the end of the year to begin with. we hope you will give to the Subject your most favourable View we Remane dear sir your most Obt Servts Respectfully

|

On April 5, 1866, a man named Robert Williams wrote this letter to the Florida Freedmen’s Bureau assistant commissioner on behalf of himself and six other Black grocers in Tallahassee. They called for an end to high taxes levied against them to support former Confederates. Bureau records do not contain a response from the assistant commissioner.

georgia

| I wish you could look in upon my school of one hundred and thirty scholars. There are bright faces among them bent over puzzling books: a, b, and p are all one now. But these small perplexities will soon be conquered, and the conqueror, perhaps, feel as grand as a promising scholar of mine, who had no sooner mastered his A B C’s, when he conceived that he was persecuted on account of his knowledge. He preferred charges against the children for ill-treatment, concluding with the emphatic assurance that he knew a “little something now”. . . . We learn from the record kept at the Freedmen’s Bureau, that there are two thousand two hundred children here. Some six or seven hundred are yet out of school. The freedmen are interested in the education of their children. You will find a few who have to learn and appreciate what will be its advantage to them and theirs. The old spirit of the system, “I am the master and you are the slave,” is not dead in Georgia. For instance, the people who live next door owned slaves. They are as poor as that renowned church mouse, yet they must have their servant. Employer and employed can never agree: the consequence is a new servant each week. |

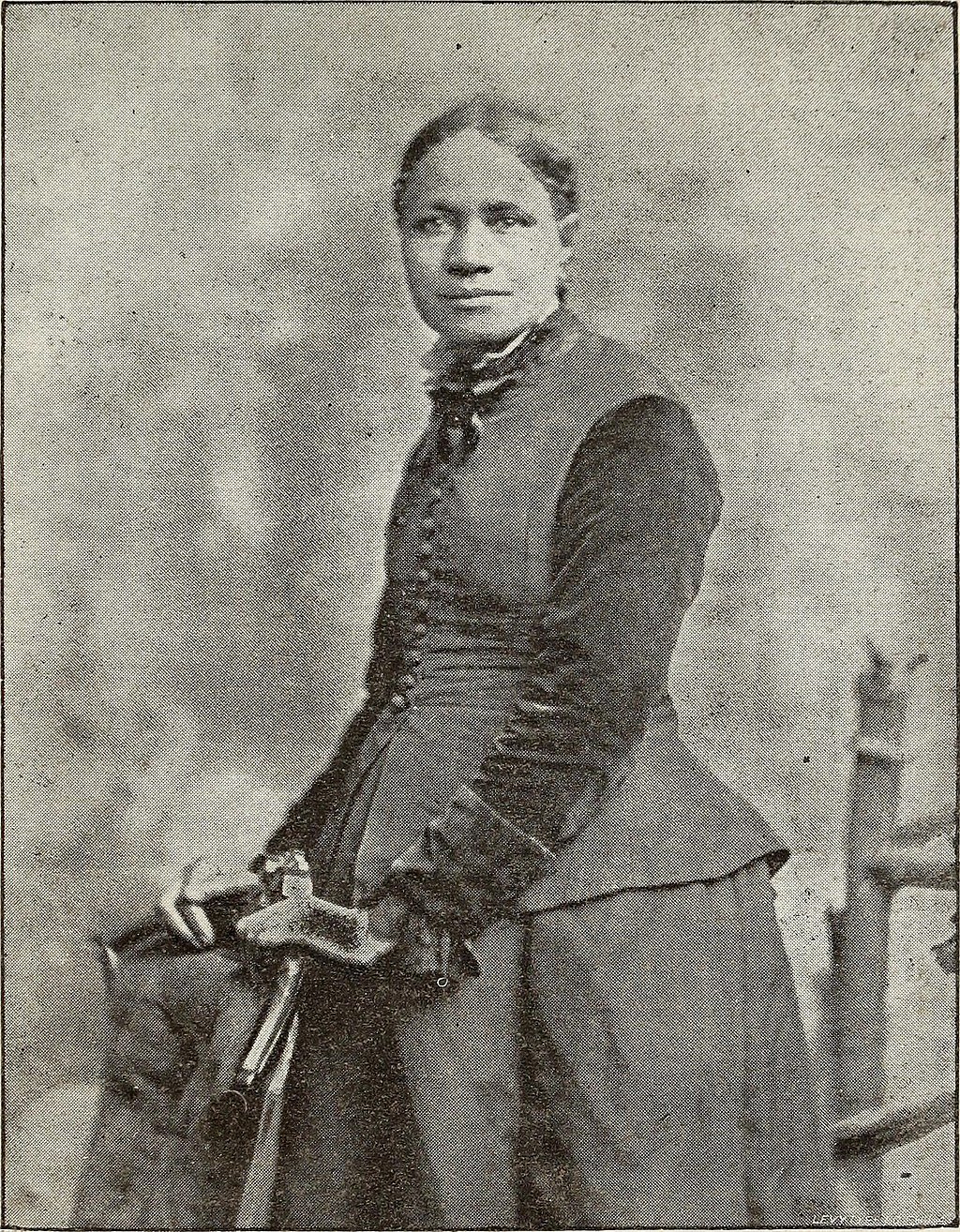

Louisa Jacobs (1833-1917)

Source: Creative Commons

In the 1860s, Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, and her daughter, Louisa, educated hundreds of formerly enslaved children. They established multiple Freedmen’s Schools, including one in Savannah, Georgia, that Louisa described in this March 1866 letter. She wrote of the Black community’s dedication to formal education and fair labor, as white neighbors clung to the prospect of re-enslavement.

Source: Documenting the American South

Hawaiʻi

During the later years of Reconstruction, the federal government withdrew military power from the South and increasingly channeled it into western U.S. expansion and settler colonialism. Non-native white officials and industrialists in Hawaiʻi made plans to monopolize the islands’ sugar trade and other resources, increasingly pushing for annexation. In January of 1893, U.S. troops invaded the capital city of the Hawaiian Kingdom and incited a coup.

They immediately helped these pro-annexation, non-native residents overthrow Queen Liliʻuokalani, who had recently issued a new constitution that would expand suffrage for native Hawaiians. As the United States moved toward annexation, the islands’ Indigenous people organized to assert Hawaiian sovereignty.

This image shows one page of a petition that more than 21,000 native Hawaiians — over half of the islands’ Indigenous population — signed in 1897 to protest annexation. The United States annexed Hawaiʻi the following year.

Source: DocsTeach

idaho

| African Americans arriving in Idaho with hopes of escaping white racism must have been in large measure disappointed. It is true that Idaho’s white legislators in the territory’s early days decided that the number of African Americans was so small that no specific “Jim Crow” laws would be needed. However, African Americans were lumped in with other “persons of color” in the restrictive statutes such as curfew laws that were enacted all over the state, principally aimed at the more numerous Chinese populations. |

In late 19th-century Idaho, white legislators targeted a growing population of Chinese immigrants with discriminatory laws to drive them out of the territory. Such measures served as a white supremacist catch-all, restricting the freedoms of people of color across Idaho.

Source: “Idaho Ebony: The African American Presence in Idaho State History” by Mamie O. Oliver

IllinoIs

In 1874, the Illinois General Assembly passed this bill, titled “An Act to Protect Colored Children in their Rights to Attend School.” It mandated free public education for Black children in the state, including penalties for denying them access, but did not call for school integration. The number of Black children attending public school increased greatly after this bill passed, but often in segregated and inadequate schools.

Source: Office of the Illinois Secretary of State

INDIANA

| The day after the Civil Rights Act passed Congress, in Lafayette, Indiana, a Black man named Isaac Barnes sued his employer, a hotel owner, for wages owed. The employer's lawyer claimed that Barnes was illegally residing in the state and therefore had no authority to make or enforce contracts there, and was not entitled to his wages. Were the racist settlement provisions in the Indiana Constitution still enforceable? A justice of the peace agreed with Barnes that they were not. The employer appealed to the county court, and there too he was defeated. . . . The judge observed that the Indiana Supreme Court had upheld explicitly racist laws in the past, as had the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott. But, he argued, the Thirteenth Amendment had changed everything. Citing other people's doubts about the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act, he rested his decision on the amendment, which, he said, had swept away the “vile system” of slavery and required that “all the wrongs and oppressions built upon the wretched institution must cease.” Barnes, he concluded, was “a citizen of the United States,” fully entitled to the fruits of his labor. |

Indiana was the last Old Northwest state with traditional anti-Black laws intact, and they were still on the books when the Civil Rights Act of 1866 passed Congress. Lafayette’s Isaac Barnes promptly used the power of this federal legislation to make gains at state and local levels.

Source: Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement, From the Revolution to Reconstruction by Kate Masur

iowa

| We ask that the word “white” be stricken from the Constitution of our State; that the organic law of our State shall give to suffrage irrevocable guarantees that shall know of no distinction at the polls on account of color; and in this we simply ask that the “two streams of loyal blood which it took to conquer one, mad with treason,” shall not be separated at the ballot-box; that he who can be trusted with an army musket, which makes victory and protects the nation, shall also be trusted with that boon of American liberty, the ballot, to express a preference for his rulers and his laws. |

Alexander Clark (1826-1891)

Source: State Historical Society of Iowa

Barber and lawyer Alexander Clark, the son of two formerly enslaved people, spoke these words at a Colored Convention in Des Moines, Iowa, in February of 1868. He called on the state legislature and voters to amend Iowa’s constitution, removing the word “white” from its voting laws. Black suffrage became legal in Iowa shortly thereafter. That same year, Clark sued the Muscatine Board of Education for denying his daughter admission to a white-only school and won his case in the Iowa Supreme Court, which declared school segregation unconstitutional.

Source: State Historical Society of Iowa

KANSAS

This photo from the early 1880s shows the Summer family posed in front of their new house in Kansas. In the 1870s and 1880s, many Black “Exodusters” left the South for Kansas, the home state of abolitionist John Brown. Exodusters found some security and success in urban and rural areas alike, but Northern industrialists had already seized vast tracts of the best farmland and left them with few opportunities in agriculture. These land claims were made possible by policies that had recently, and often in violation of federal treaties, forcibly removed Native people from the land.

Source: Kansas Historical Society

KENTUCKY

| Application of the Colored People of Shellyville To Secretary Stanton Washington D.C.

Secretary we as a people ask for our wright– we acknowledge that we are Free But where is it That we are not be aloud to enter in to Publice Business Here in Shellyville. . . . we are not aloud to open know Grocery know Coffee House know kind and if we wont sperrits for sickness make know odds how Bilous the case we cannot get it if you call this Freedom what do you call Slavery I hop that we have some Friend in the capital the soldiers have Been in the army and are now mustered out and come Back home and thery cannot enter any Business whatever But have to return to their old master and work for whatever they chosse or see proper to gave them some get $10 dollars some $12 dollars some $13 whom can live that way Please send some word to our relievf. . . . Henry Mars |

On May 14, 1866, former Sergeant Major of the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry Henry Mars wrote to the Secretary of War on behalf of his community in Shelbyville, Kentucky. He noted restrictions on their freedoms — including no entry to grocery stores, coffee houses, other ostensibly public businesses — and requested assistance. Records indicate that the War Department forwarded this letter to the Freedmen’s Bureau, but include no documented reply.

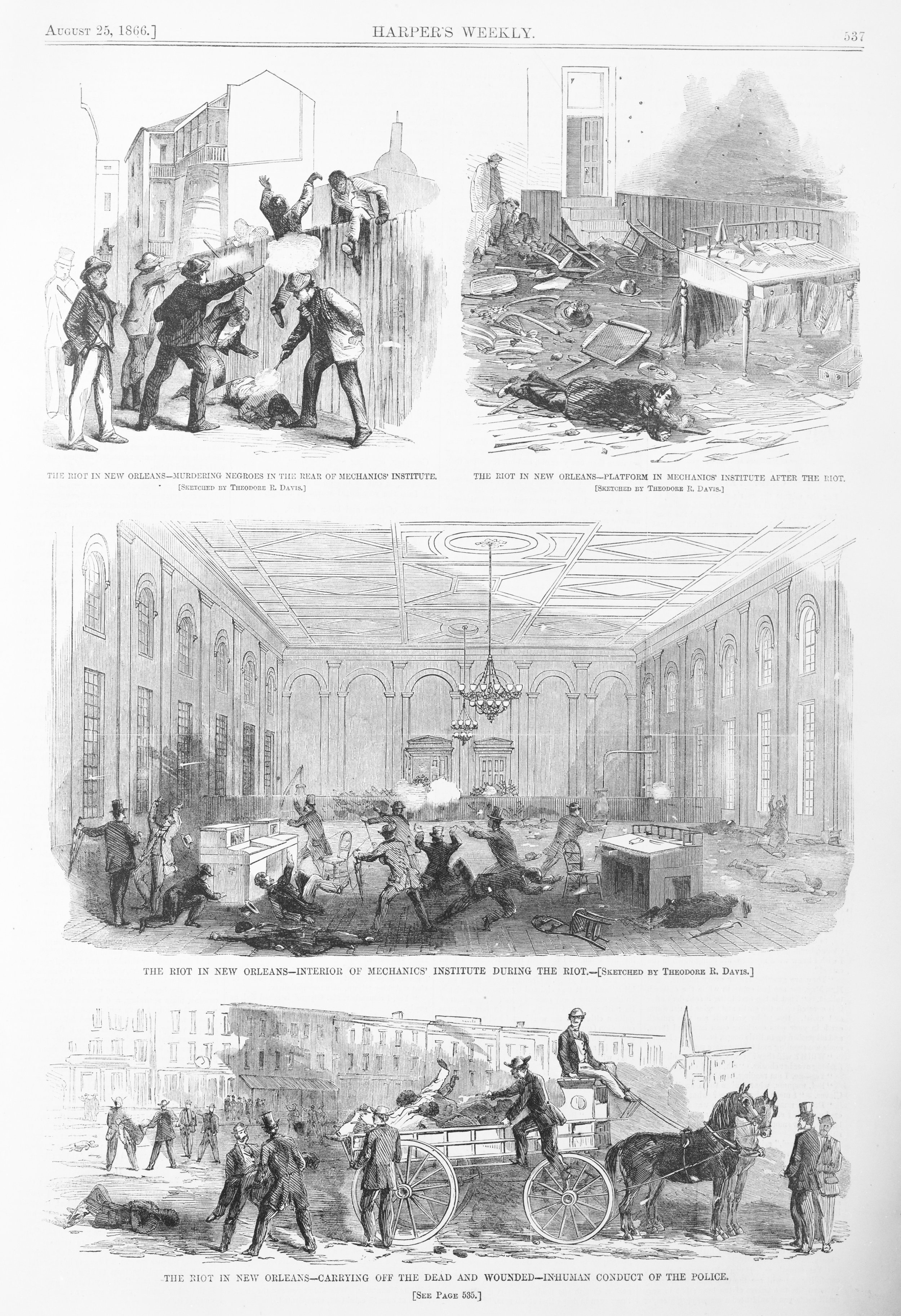

Louisiana

By 1866, the Louisiana state legislature had begun implementing Black Codes and preventing Black enfranchisement. The constitutional convention reconvened on July 30 at the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans to discuss the prospect of voting rights for Black residents. A mob of white supremacists — including city police and firemen, supported by the mayor — descended on the convention and opened fire. They killed approximately 50 people, most of whom were Black, and injured over a hundred. They were not charged with murder. Sketched here in vignettes, the Mechanics Institute Massacre affirmed that Black people needed concrete protections against former Confederates and galvanized the Republican Party to push through the Reconstruction Acts.

Source: Library of Congress

Maine

Click image to make larger.

This broadside advertised an annual fundraising festival organized by an African Methodist Episcopal church in Portland, Maine. The November 1874 event included exhibitions and concerts starring children in the congregation, with a variety of refreshments served throughout.

Maryland

David B. Simons, pictured here with his wife, Margaret, was born into slavery in Maryland and emancipated in the 1850s. During Reconstruction, he became a founding member, school teacher, and trustee of Tolson’s Chapel, a Methodist church in Sharpsburg. The local Black community prioritized formal education for their children, coordinating with the Freedmen’s Bureau to open a school. Simons’ son, James, attended school and taught at Tolson’s Chapel, where he eventually became a preacher. The chapel would serve as Sharpsburg’s public school for Black students until 1899, when a new schoolhouse opened nearby.

Source: National Park Service

Massachusetts

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and her daughter, Florida Ruffin Ridley, established The Woman’s Era in 1894. Founded in Boston, Massachusetts, it was the first national newspaper for and by African American women. The Woman’s Era grew out of the Woman’s Era Club, a local civic organization dedicated to community uplift through service, education, and other social provisions. Often excluded from white women’s political projects, Black clubwomen produced and discussed monthly articles on politics, fiction, and social and domestic issues published in The Woman’s Era. Ruffin and Ridley are pictured here in the April 1895 issue. That same year, their local club organized the first National Conference of the Colored Women of America.

Source: Internet Archive

Michigan

Pictured here is Fannie Richards, a teacher who fought against school segregation in Detroit during Reconstruction. In the late 1860s, a local school prohibited a Black man named Joseph Workman from enrolling his son — even though they lived in the neighborhood and paid school taxes. Richards helped bring Workman v. Detroit Board of Education to the Michigan Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Workman and school desegregation. In 1871, Richards became the first kindergarten teacher at Everett Elementary School, the city’s first integrated school, where she worked for the next four decades.

Source: Michigan Radio

Minnesota

| Black adults may have represented threats to low-skilled or unskilled white laborers, but it was Black children who seemed to pose the worst threat by personifying the future of Blacks in St. Paul. Accordingly, in August 1865 the school board “almost unanimously” passed a resolution challenging the racial mingling which had been "to some extent permitted" in the schools and again instructed the superintendent to provide “a suitable teacher and accomodations” for Black children. It further resolved that “no children of African descent be thereafter admitted to any other public school.” In October official notice was given that a “School for Colored Children” would open in Morrison's Building at Ninth and Jackson Streets (although furniture was not yet available). . . . Soon after classes began, however, the board of education discovered “problems of maintaining and operating” the school. (No such problems apparently existed in the city's three established schools — Washington, Adams, and Jefferson — and one new German-English school, where a total of 1,241 students were enrolled). |

In the early months of Reconstruction, the school board in St. Paul, Minnesota, designated a separate and unequal school for Black children. With minimal funding and supplies, this school was dilapidated — unable to even provide sufficient shelter to students from the city’s harsh winter weather. Attendance dwindled over the next few years. In 1869, however, state legislators responded to years of petitions and other advocacy efforts from Black Minnesotans and legally ended school segregation.

Source: “Race and Segregation in St. Paul’s Public Schools, 1846-69,” by William D. Green

Mississippi

| My Dear Wife: Yours is just received. I am glad to hear from you again. I can not send you any money now, because it is too unsafe, unless I can see some one going there. You had better try and make your arrangements to come out here to me. I think I can do well here. My master has good land. He has agreed to let us go and work it. He provides all the stock, farming utensils and land, and gives us half we can make. I am not able to go there now. so come out and bring all your children, and tell Neverson and William to Come. We can all do better here than we can there. Give my love to cousin Randall Quarles, and tell him his brother Wash is still with Master. We have plenty to eat here, good Clothes, and have found work generally. Remember me to father, my brothers, and all my friends. Write me again soon. Your affectionate husband, Moses Scott. |

On Dec. 17, 1865, a formerly enslaved man working on a plantation in Mississippi wrote this letter to his wife in Virginia. According to Freedmen’s Bureau records, Moses Scott and his wife Lily Ann had been separated and were trying to settle together in a place with means to provide for their family. No Bureau records indicate whether or not the couple reunited.

Missouri

On Dec. 27, 1873, The Weekly Caucasian in Lexington, Missouri, published this announcement on behalf of a local Black Baptist church pastor. The notice described an ongoing festival organized by the congregation to raise money for their church.

Montana

| The education of children of African descent shall be provided for in separate schools. Upon the written application of the parents or guardians of at least ten such children to any board of trustees, a separate school shall be established for the education of such children, and the education of a less number may be provided for by the trustees, in separate schools, in any other manner, and the same laws, rules, and regulations which apply to schools for white children shall apply to schools for colored children. |

In 1872, Montana’s legislative assembly produced a series of acts organizing the territory. A law on public schools included this section mandating school segregation.

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library

Nebraska

This 1887 photo shows the Shores family posed in front of their sod house in Nebraska. Jerry, seated second from the right, was enslaved just decades prior. According to the Nebraska State Historical Society, the younger family members became noted musicians. The Shores were among many African Americans who left the South in the 1870s and 1880s, moving to the Great Plains in search of land to call their own. To the extent that land was available, however, it was only because of policies that had recently, and often in violation of federal treaties, forcibly removed Native people from the area.

Source: Library of Congress

Nevada

| I say it is within the power of the Nevada Legislature to enact such a law without acting in hostility to the Fifteenth Amendment, and I suppose I violate no confidence now in stating that the original draft of that amendment, as reported by Governor Boutwell, of Massachusetts, to the Reconstruction Committee of the Fortieth Congress, contained the words “nativity and religious belief.” I chanced to be present in Washington, although not then a member of this House, and represented to Mr. Boutwell that with the words “nativity and religious belief” in we could not exclude the Chinese from the ballot if we should so desire, and Nevada would not in my opinion ratify the Fifteenth Amendment if it should be so framed as to prohibit the exclusion of the Chinese from the right of suffrage. The language of the Fifteenth Amendment was subsequently modified and the words “nativity and religious belief” were stricken out. |

On March 1, 1869, Nevada became the first state to ratify the 15th Amendment. State lawmakers agreed to extend suffrage to Nevada’s very small African American population, but opposed voting rights for the state’s much larger Chinese American population. On June 9, 1870, The Gold Hill Daily News published recent remarks from Representative Thomas Fitch, excerpted here. Fitch recounted that Congress removed “nativity and religious belief” from the Fifteenth Amendment before Nevada ratified it, thereby allowing local officials to prohibit Chinese American suffrage.

Source: Newspapers.com

New hampshire

| Portsmouth’s Black citizens had been members of local churches since the 1700s, but there is no evidence of their attempting to establish a church of their own until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. A first, if not lasting, attempt was made in 1873. Under the leadership of Edmund Kelly a group of Portsmouth’s Black citizens gathered for worship in the Baptist tradition at the South Ward Room. The gathering flourished briefly. Then Kelly was “unavoidably called away” to Massachusetts. The group continued under the guidance of Elder John Tate. When Tate died a short time later services ceased. Not long after, Kelly returned to Portsmouth. . . . in 1879 Kelly reconvened Portsmouth’s fledgling church. |

Black residents of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, started to assemble their own church in the early 1870s. In the 1880s, a community known as the People’s Mission grew into another Black church organization that sustained services and programs well into the 20th century.

Source: Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage by Mark Sammons, Valerie Cunningham

New jersey

| Mr. Bradley, the founder of Asbury Park, has been moved to protest against what he calls the monopolizing of the seats by these colored sojourners, who, in their turn, have held a meeting to denounce him for undertaking to interfere with their rights. Of course if the seats are provided for the public, the colored people have as much right to them as the white people, so long as they conduct themselves properly. First come first served must be the rule, and whoever finds an empty seat is at liberty to take it, whatever his complexion. Nor even if they are private property is it possible to make any reasonable discrimination against their use by decent colored people in a place like Asbury Park. Yet it seems that the white visitors, even when they are fellow Methodists, are outraged when they find the privileges of the beach largely enjoyed by the colored visitors. They are willing that they should get food for their souls at the camp meetings, and are not averse to employing them as servants, but they do not want to sit by them on the board walk. |

During Reconstruction, New Jersey vacation destinations drew white and Black visitors alike. Many white tourists opposed sharing spaces of leisure with Black patrons and, in the 1880s, some local officials tried to implement segregated facilities and vacation times. In a June 29, 1887, article from The Sun, excerpted here, the author described white outrage at the idea and practice of Black recreation in Asbury Park.

Source: Chronicling America

New mexico

Click image to make larger.

This image shows the first page of the 1868 treaty between the U.S. and the Navajo in present-day New Mexico. During the Civil War and Reconstruction, the increasingly powerful federal government destroyed Southwestern Native settlements and seized land in the name of U.S. expansion and “civilization.” Surrounded by this settler colonial enterprise and battling terrible living conditions, the Navajo at Bosque Redondo organized a meeting with federal officials in an effort to retain their sovereignty. With this treaty, the Navajo agreed to live within a designated reservation, enroll their children in English-speaking schools, and allow forts and rail lines on their land, among other concessions. They also persuaded the U.S. to recognize their sovereignty, becoming the only Native Nation to prevent removal from their homelands through a treaty.

New york

On Dec. 13, 1872, hundreds of African Americans convened in New York City for the first meeting of the Cuban Anti-Slavery Committee. Cofounder Samuel Raymond Scottron read aloud a series of resolutions condemning the Spanish government for its enslavement of Cubans and delivered a speech, excerpted here. Reverend Henry Highland Garnet was the keynote speaker. By this time, Cuba had become one of the last countries to maintain slavery as a domestic institution, and protests from Cuban nationalists had ignited a revolution. The committee expressed a sense of responsibility and solidarity to those with fewer freedoms, drawing on a long history of Black activism in domestic and transnational anti-slavery societies as they championed Cuban revolts against enslavement.

Source: Colored Conventions Project

Henry Highland Garnet (1815-1882)

Source: Creative Commons

| Shall the four million in our own land, who have so lately tasted of the bitter fruit of slavery, stand idly by while a half million of our brethren are weighed down with anguish and despair at their unhappy lot? or shall we rise up as one man and with one accord demand for them simple and exact justice? Indeed, we look back but a very brief period to the time when it was necessary for other men to hold conventions, appoint committees and form societies, having in view the liberation of four millions among whom were ourselves; but, thanks to the genius of free government, free schools and liberal ideas, all the outgrowth of an enlightened and Christian age, we are enabled in the brief space of ten years to stand, not only as freemen ourselves, but with voices and with power to demand the liberation of five hundred thousand of our brethren, who are afflicted with the curse of human slavery. |

North carolina

| By 1869, the chairman of the Committee of Freedmen’s Affairs estimated that smallpox had infected roughly 49,000 freedpeople throughout the postwar South from June of 1865 to December of 1867. This statistic tells only part of the story. Records of Bureau physicians in the field suggest that the numbers in their specific jurisdictions were, in fact, much higher. . . . Due to the countless freedpeople in need of medical assistance, many Bureau doctors claimed to be unable to keep accurate records. “I am unable to forward the consolidated reports of the sick freedmen for the month of February,” wrote a Bureau doctor from North Carolina. . . . In rural regions and in places where the Bureau did not establish a medical presence, cases went unreported. When the smallpox epidemic hit the area surrounding Raleigh, North Carolina, in February 1866, two freedwomen “walked twenty-two miles” in search of rations and support. The unexpected cold weather combined with the outbreak of smallpox in the state capital, however, depleted the Bureau’s supply reserve. After discovering that even the benevolent office had “only empty barrels and boxes,” and “nothing of real service to offer,” the women wept. Statistics fail to convey the great emotion and fear that the so-called pestilence incited among those living in the postwar South. |

In the 1860s, a smallpox epidemic erupted and devastated Black populations across North Carolina and throughout the South. The federal government largely neglected the medical crisis with ill-equipped, ineffective Freedmen’s Bureau hospitals and personnel.

Source: Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction by Jim Downs

North dakota

On July 16, 1873, The Bismarck Tribune in present-day North Dakota published an article called “The Indian Policy.” The author justified federal policies to expand settler colonialism and destroy Indigenous sovereignty, framing these actions as promoting “civilization.” He echoed Republican elites and industrialists, who used broad Reconstruction-era discussions of U.S. reconciliation, citizenship, and racial inclusion to justify campaigns for westward invasion and extraction. When this article was published, the federal government had just broken its 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie with the Sioux — invading their designated land in the Black Hills to capitalize on the discovery of gold. It ends with this excerpt, describing the Sioux as “incorrigibly hostile,” and whose further displacement might bring “an honest move towards their civilization.”

Source: Chronicling America

OHIO

| You say you have emancipated us. You have; and I thank you for it. You say you have enfranchised us. You have; and I thank you for it. But what is your emancipation? What is your enfranchisement? What does it all amount to, if the black man, after having been made free by the letter of your law, is unable to exercise that freedom, and, after having been freed from the slaveholder’s lash, he is to be subject to the slaveholder’s shot-gun? Oh! you freed us! You emancipated us! I thank you for it. But under what circumstances did you emancipate us? Under what circumstances have we obtained our freedom? Sir, ours is the most extraordinary case of any people ever emancipated on the globe. I sometimes wonder that we still exist as a people in this country; that we have not all been swept out of existence, with nothing left to show that we ever existed. . . . When you turned us loose, you gave us no acres: you turned us loose to the sky, to the storm, to the whirlwind, and, worst of all, you turned us loose to the wrath of our infuriated masters. |

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

Source: National Portrait Gallery

Writer, orator, and activist Frederick Douglass addressed the Republican National Convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, in June of 1876. With these words, he interrogated the meaning of “emancipation” and “enfranchisement” to the many white Republicans who had begun their retreat from Reconstruction.

Source: Making of America

Oklahoma

| The establishment of churches and schools symbolized the determination of Indian freedpeople to create their own communities in the face of threats and violence during this liminal period in which they waited to be adopted as citizens of Indian nations and find out whether they would receive land they had applied for. Both their land and their citizenship depended on the Five Tribes and the United States upholding their treaty promises to them. These schools and churches formed the crux of communities that emphasized Black autonomy, allowing Indian freedpeople to create Black spaces within Indian nations. |

“Indian freedpeople” refers to Black people formerly enslaved by members of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Nations. Known together as the Five Tribes, these Indigenous nations attempted to maintain sovereignty and slavery in present-day Oklahoma after the Civil War, as the U.S. government encroached and forced legal emancipation. Within this struggle, Indian freedpeople navigated a liminal space between the reality of their enslavement and the promise of true liberation. They understood access to land as critical to tangible, sustainable freedom, pursuing tribal citizenship, negotiating with U.S. officials, and organizing their kinship networks to claim land. In this region, unlike many others, these efforts often succeeded.

Source: I've Been Here All the While: Black Freedom on Native Land by Alaina E. Roberts

Oregon

| It is tempting to dismiss questions about African American citizenship as irrelevant to postwar Oregon. After all, just 346 people of African descent lived in the state by 1870. When viewed in the larger frames of Oregon’s multiracial society and longstanding white supremacist legal regime, however, the threat posed by African American citizenship becomes clearer. White Oregonians worried that the seemingly imminent enfranchisement of African Americans at the federal level might lead to sweeping laws that prohibited all discrimination on the basis of race or color. African Americans may have been scarce in the Pacific Northwest, but Oregon was a multiracial state and home to thousands of American Indians, Chinese newcomers, Hawaiians, and mixed-race people. Oregon’s prewar laws excluded most of those non-white residents from exercising the rights and privileges of citizenship. At stake in the national debate over African American citizenship was the question of whether Oregon, or any state, could continue to make whiteness a central qualification for civil equality and political participation. |

In the 1860s and ‘70s, white Oregonians reaffirmed the state as a hostile place for African Americans to settle and barred thousands more people of color from civic life and citizenship rights. A Democrat-dominated state legislature took office in 1868 and quickly rescinded ratification of the 14th Amendment, which would not be ratified again until 1973.

Source: “Oregon’s Civil War: The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest” by Stacey L. Smith

pennsylvania

| The great problem to be solved by the American people, if I understand it, is this: Whether or not there is strength enough in democracy, virtue enough in our civilization, and power enough in our religion to have mercy and deal justly with four millions of people but lately translated from the old oligarchy of slavery to the new commonwealth of freedom; and upon the right solution of this question depends in a large measure the future strength, progress and durability of our nation. . . . Less than twenty five years ago slavery clasped hands with King Cotton, and said slavery fights and cotton conquers for American slavery. Since then slavery is dead, the colored man has exchanged the fetters on his wrist for the ballot in his hand. . . . And yet, with all the victories and triumphs which freedom and justice have won in this country, I do not believe there is another civilized nation under heaven where there are half as many people who have been brutally and shamefully murdered, with or without impunity, as in this Republic within the last ten years. . . . Our work in this country is grandly constructive. Some races have come into this world and overthrown and destroyed. But if it is glory to destroy, it is happiness to save; and oh, what a noble work there is before our nation! . . . Women, in your golden youth; mother, binding around your heart all the precious ties of life, let no magnificence of culture, or amplitude of fortune, or refinement of sensibilities, repel you from helping the weaker and less favored. If you have ampler gifts, hold them as larger opportunities with which you can benefit others. |

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825-1911)

Source: Internet Archive

On April 14, 1875, writer, orator, and activist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper spoke in Philadelphia at the Centennial Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. In her address, excerpted here, Harper acknowledged the progress made during Reconstruction, the violent attempts to undo that progress, and the work still needed to fulfill the promise of freedom. She noted the shortcomings of white people and political parties who claimed allyship, and urged African Americans to continue organizing for justice. At the end of her remarks, Harper encouraged Black women, specifically, to carry the movement forward.

Source: BlackPast

rhode island

| Some Northern Blacks felt so betrayed and devastated by white indifference toward the welfare of African Americans that they could see virtually no hope for a brighter future. Writing to William Lloyd Garrison as “an able, consistent and influential friend of the colored race” following the 1876 election, Downing and several other Blacks in Newport, Rhode Island, poured out their pain and sadness about how Northern white Republicans they trusted and respected had turned their backs on African Americans. “We are depressed,” they confessed to Garrison, “things seem sadly out of joint; we are sick at heart through hope deferred. The declarations and advancements in civilization that are true of our country and that may be referred to make our condition deplorable. They make us more sensible as to the outrage we endure.” While these men were all too familiar with hatred and poor treatment from whites, what distressed them most was the indifference to their rights shown by leading New England men who had once been their collaborators and friends. African Americans could, they acknowledged, endure, “with a certain degree of complacency,” the insults they were constantly subjected to, but “the indifference as to the weak, as to our rights, and sympathizing with those who are outraging us. . . . make cold chills come over us.” |

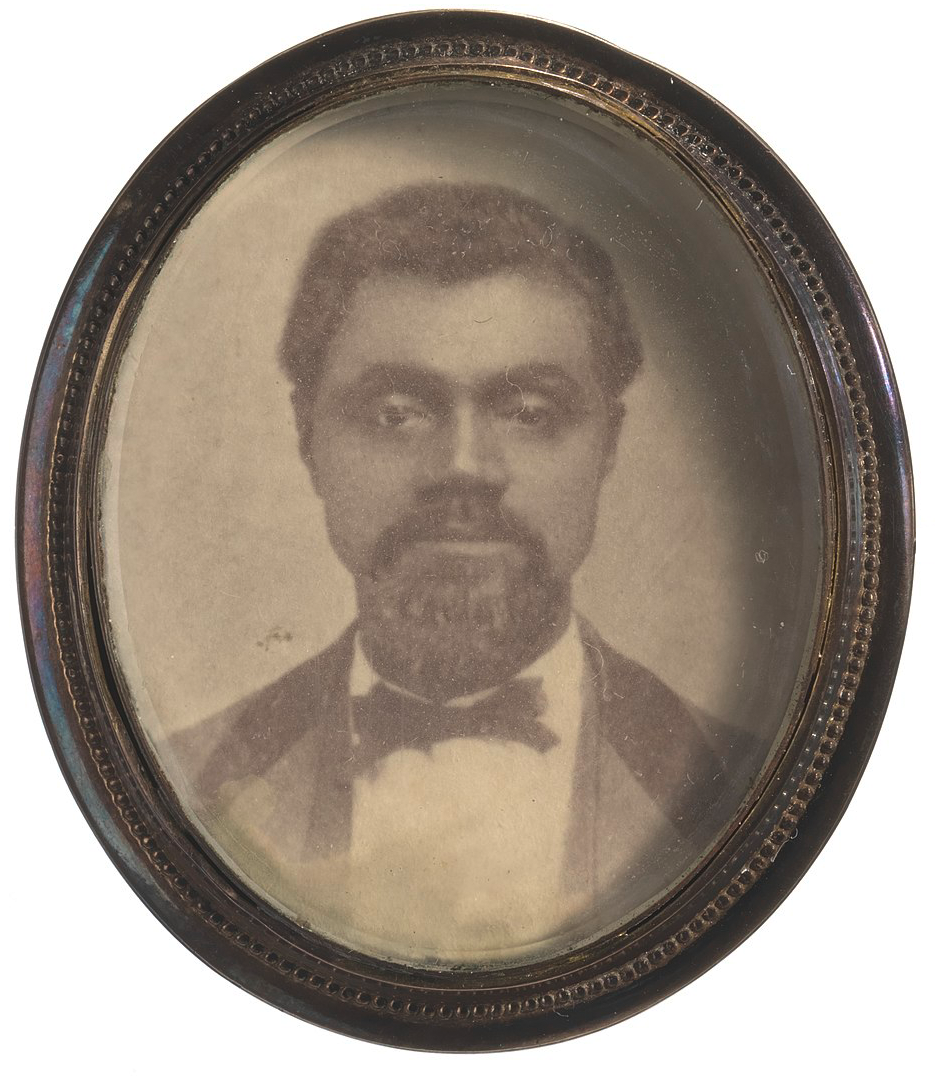

George Thomas Downing (1819-1903)

Source: New York Public Library

A coalition of Black Rhode Islanders, including restauranter and civil rights activist George T. Downing, lamented the disloyalty of white political leaders in New England who revoked their support for Reconstruction in the mid-1870s.

Source: “We Will Be Satisfied With Nothing Less”: The African American Struggle for Equal Rights in the North during Reconstruction by Hugh Davis

South Carolina

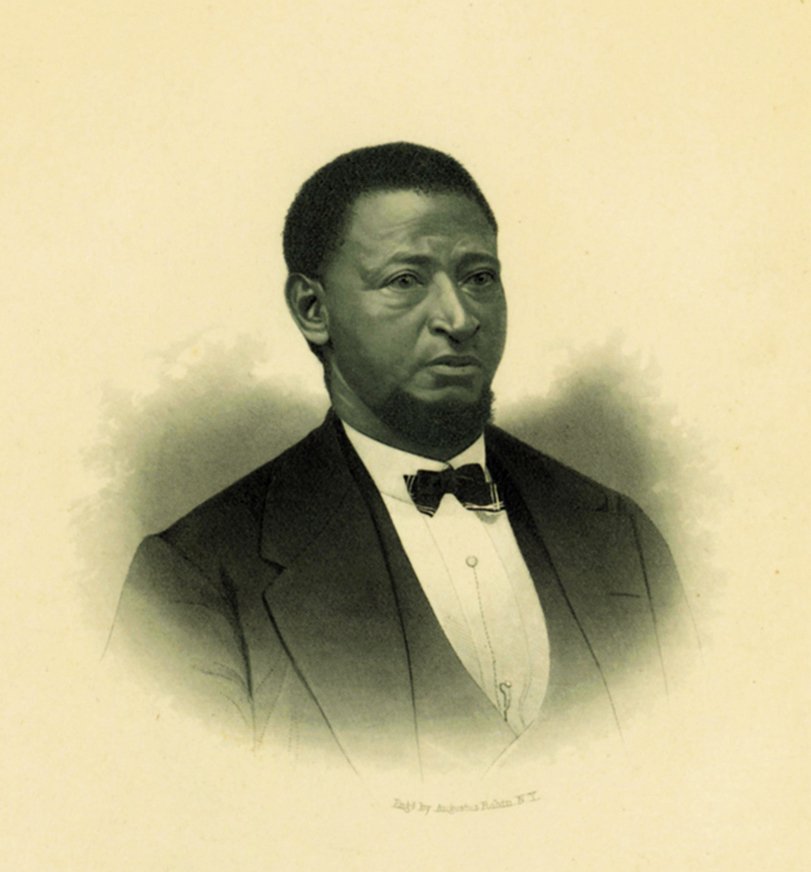

On April 23, 1866, William Beverly Nash and several other freedmen in Columbia, South Carolina, wrote to the local Freedmen’s Bureau acting assistant commissioner. They outlined major discrepancies in medical care for Black and white patients afflicted with smallpox, and asked the federal government to intervene on behalf of their community. According to Bureau records, the assistant commissioner forwarded this petition to several parties, including the Bureau’s surgeon-in-chief. A follow-up letter between Bureau surgeons suggested that local agents had addressed these complaints by early May, but the extent of their work remains unclear. Two years later, Nash was elected to the state Senate and played a pivotal role in developing a new, progressive constitution for South Carolina.

William Beverly Nash (1822-1888)

Source: Creative Commons

We would ask if there is no help or Relief for the Shameful treatment that our people are now receiving at the Small Pox Hospital, in this City. We beg to make a few Statements for your information. There was at one time nineteen men, Six woman & four children Sick in one room with Small Pox, there was also one white man, who had a room to himself while all of the 29 persons of Color, was in one room, with no person to nurse or cook for them, thay had to cook for themselves. No tea or other noureshments for them. with the Exception of Sour meal. We appeal to you as the representative of the Goverment and beg you to foward this our petition on to Gen Howard and See if Something cannot be done for our Suffering people. . . . will you not interpose in our behalf untell we can appeal to the Commissioner Gen Howard at Washington and the Great head of the Goverment to assist us in this the hour of our distress, which is Great just at this time. . . .

|

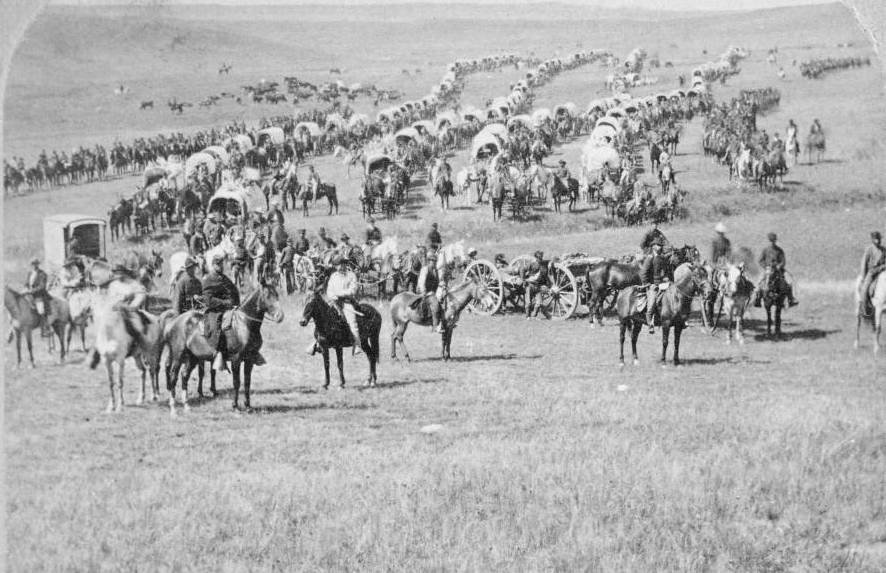

south dakota

This 1874 photo shows U.S. artillery, cavalry, and wagons traversing present-day South Dakota. They were invading Sioux territory in order to capitalize on the discovery of gold in the Black Hills. Federal officials promptly broke the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which had exclusively designated this area for Sioux settlement as part of the Great Sioux Reservation. Both the original treaty and reneging indicated the rapid destruction of Indigenous sovereignty at the hands of increasingly powerful Republicans and industrialists. During Reconstruction, they used broad discussions of U.S. reconciliation, citizenship, and racial inclusion to justify settler colonial initiatives and claims over capital. The Black Hills expedition searched for gold and prepared to enforce U.S. mining settlements, catalyzing the Great Sioux War between local Indigenous groups and U.S. invaders. In 1877, the federal government seized the Black Hills and, decades later, carved Mount Rushmore into them.

Source: DocsTeach

tennessee

On April 28, 1866, a Black couple formalized their marriage in Lebanon, Tennessee. Thomas Harris and Jane Harris (Shute) had lived and raised a family together for almost 15 years, but could not legally marry until Reconstruction. This marriage certificate from the Freedmen’s Bureau notes their commitment predating the Civil War, as well as the names and birth dates of their eight children.

texas

On May 11, 1867, a freedman in Galveston, Texas, named Hawkins Wilson asked the Freedmen’s Bureau for assistance in finding his relatives. He had last seen his sisters in Virginia in the 1840s, just before an enslaver separated them and took Wilson to Texas. In this letter, Wilson noted the names of his relatives, their enslavers, and last-known locations to aid Bureau agents in their search. He emphasized his desire to reunite with his sisters, but did not know if they were still alive. It is not clear if Wilson and the Bureau ever located his family.

Source: Rice University

UTAH

Click image to make larger.

On Aug. 1, 1882, a Black musical ensemble called the Jubilee Singers performed at an opera house in Ogden, Utah. The group formed at Fisk University, a historically Black college in Tennessee, and first toured in 1871 as a school fundraising effort. They quickly gained popularity and introduced people around the country to African American musical traditions, like spirituals, disrupting white perceptions of Black musicians promoted at racist minstrel shows. This Ogden Herald clipping described their 1882 tour stop as a riveting concert for Utahns.

Source: Utah Digital Newspapers

VERMONT

| The overshadowing question of the day is that of negro suffrage. The large majority of Republicans feel that reconstruction without giving the negro the ballot, will deprive us of the laurals fairly won in battle by patriot blood, and leaves the negro question still unsettled. It matters not that the negro does not vote in all the free states, that even in some of the states of New England, the law is partial and unjust. . . . The Southerners to day, believe that without the aid of the blacks, the North could not have conquered. They are exceedingly mad against them, and if the negro is not allowed the ballot they will oppress him all they dare, and more than will be safe for it will lead to resistance, to endless trouble, to quarrels, and the shedding of blood, and the peace which we have all been praying for will not come. . . . All the silly twaddle about the negro voting as the master directs, may go for what it is worth. We remember how in years gone by that we were repeatedly told that the negro would only fight for his master. Strange that you cannot beat the truth into some skulls. |

On June 30, 1865, The Vermonter in Vergennes, Vermont, published an editorial on Black suffrage. In this excerpt, the author argued that African Americans in the South were loyal to the U.S. during the Civil War and deserved the power and protection of political representation. He also noted the importance of Black suffrage to Republican aims for Reconstruction in the South, even as some states in New England continued to bar African American residents from voting.

Source: Newspapers.com

Virginia

| We now, as a people desires to be elevated, and we desires to do all we can to be educated, and we hope our friends will aid us all they can. . . . I may state to all our friends, and to all our enemies, that we has a right to the land where we are located. For why? I tell you. Our wives, our children, our husbands, has been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now locate upon; for that reason we have a divine right to the land. . . . And then didn’t we clear the land and raise the crops of corn, of cotton, of tobacco, of rice, of sugar, of everything? And then didn’t them large cities in the North grow up on the cotton and the sugars and the rice that we made? Yes! I appeal to the South and the North if I hasn’t spoken the words of truth. I say they have grown rich, and my people is poor. |

In 1866, the U.S. Army forcibly removed a Virginia freedman named Bayley Wyatt from the land he had maintained since the close of the Civil War. Shortly thereafter, at a public meeting, Wyatt protested his eviction and advocated for freedpeople’s claims to the land they inhabited.

Source: Facing History & Ourselves

washington

| As postwar Washington set out to consolidate the nation into a tighter, truer union, its efforts out West simply had no developed option that would leave room for people like the Nez Perces — historically friendly and utterly unthreatening but living by ways well outside the national mainstream — to live as they wanted while still being part of that new union. Some official like Howard might begin by saying some peaceable people should be left alone in some “poor valley,” but then came pressure to open that valley up, and then some nasty business like the killing of Wilhautyah to force a decision. At that point, authorities had no structure of ideas to accommodate anything but pulling Indians onto some reservation. Language changed. “Sympathy” and “fairness” took on new meanings. Honest men and women, sympathizers with the deplorable things happening to Indians, insisted that they be fairly paid for their land and fairly supported as they built new lives. But whether Indians would surrender their land and change their lives — that was not in the discussion. When people like the Nez Perce resisters stuck to their claims, the reaction of authorities like Howard was to feel dismayed, frustrated, and, in a deeply strange inversion, betrayed. |

When Congress terminated the Freedmen’s Bureau in the early 1870s, the federal government increasingly directed its attention and resources to settler colonial expansion and “civilization” in the West. General Oliver O. Howard, a former commander in the Union Army and head of the Bureau, rejoined the military to direct the removal of Native people to reservations in the Pacific Northwest. The Nez Perce, whose homeland included part of present-day Washington, refused to give up their sovereignty. Under Howard’s order, communications devolved into violence and Native removal in 1877. Howard and other Republican leaders had twisted principles of freedom and equality at their convenience: promoting them in the South, while effectively abandoning them in the West.

Source: The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story by Elliott West

west virginia

| Experience, a very sad experience too, has proven that this modern Radicalism grows by what it feeds upon; it is never full to satiety. Once, it asked only restrictions upon the spread of slavery; then it wanted negroes to serve in the army; then, because they had served in the army, it wanted them to be invested with citizenship; now they are to be admitted as witnesses in the courts, but does any person suppose radicalism will stop here? Tomorrow it will demand that negroes be qualified to act as jurors; the next day we will have the negro suffrage, the next absolute social equality will be conceded. . . . We have all got along very well under the old system, our courts have been able to administer justice very successfully in the past without the aid of negro testimony, and we can see no reason why any alarming catastrophe should overtake us by the continued exclusion of the negro from the courts. The introduction and passage of so unnecessary a measure at the present time shows that it is simply one manifestation of that spirit of radicalism which now rules the late Republican party. |

On Feb. 1, 1866, The Wheeling Register in West Virginia published an editorial against Black suffrage. The author decried the expanding rights of African Americans under federal law as a violation of states’ rights, catastrophizing the prospect of equality.

Source: Newspapers.com

wisconsin

| The connection between Ku-Klux and the Democratic Party often slipped between figurative analogies, indirect associations, and literal claims of a supportive relationship or even identity. The Wisconsin Democratic Party was the “Ku-Klux” party because their interests depended on the suppression of Southern Black voters. . . . This phrase “Ku-Klux Democracy” became so common, particularly in election seasons, that it must have come to feel natural to readers. Yet this strategy could backfire on Republicans. Democrats, though the minority party, had significant power in the federal government. They were also structurally equivalent to the Republican Party. If they were Ku-Klux-like, it cast a shadow on the government itself. |

In the early years of Reconstruction, white terror organizations quickly integrated into established political parties. By 1868, the Ku Klux Klan and the Wisconsin Democratic Party had forged a common identity predicated on Black voter suppression.

Source: Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction by Elaine Frantz Parsons

wyoming

In 1868, federal officials met with members of the Sioux — Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota — and Arapaho bands in present-day Wyoming. They entered into the Treaty of Fort Laramie, establishing the Great Sioux Reservation and classifying the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota as “unceded Indian territory” to resettle and consolidate the Sioux. Pictured here is the first page of the agreement. This treaty was part of a larger campaign of increasingly powerful Republican elites and industrialists to expand the westward reach of U.S. sovereignty and capital through settler colonialism. They used broad Reconstruction-era discussions of U.S. reconciliation, citizenship, and racial inclusion to promote “civilization” and justify the seizure of Native land. The United States reneged on the Treaty of Fort Laramie in the 1870s, with the discovery of gold in the Black Hills.

Source: National Archives

Click image to make larger.